History of Price Disruptions

Monday’s steep decline in the price of West Texas Intermediate (WTI) is the most visible sign of volatility in the oil market caused by the current supply and demand disruptions. As with other market disruptions, when the underlying asset prices are traded in spot and futures markets, rapid changes are possible. Most investors are used to this from stock price volatility, occasional exchange, and regulator intervention in the form of trading halts and limiting short selling. Interest rates are also affected by market disruptions and when volatility spikes the spread, or difference, between government-set rates and market-driven rates can diverge.

This happened at the end of 2008 during the financial crisis when the cost of money as measured by the US government – the Fed funds rate – and the cost of money as measured by the London Inter-Bank Offered Rate (LIBOR) as set between large banks, sharply separated peaking on October 13th, 2008. LIBOR reflected counterparty risk, as the rate-setting financial entities themselves came under question from a cash flow and even liquidity perspective.

With so many global contracts tied to LIBOR, the dislocation spread throughout the money supply affecting investments and debt instruments. Different interventions to restore liquidity worked and that spread reduced to historic norms.

The Reality of Oil and Gas

When we look at this for Oil, the reality is somewhat different. The global supply chain for oil and gas is about the movement and processing of a physical commodity. That is why there is both a limit and a lag when government and price-targeting entities like The Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) make announcements or set limits.

At the front end, the varying types of machinery used to extract the oil have different cost structures and breakeven prices, and decisions are made on what assets to shut down and for how long based on projections that go beyond the spot price or May futures. Given that there are actual physical assets and people involved and affected, this makes sense, whether jointly operated, owned or leased, contracted, or directly employed.

Similarly, distribution, storage, and processing assets are real physical and geographically fixed other than certain marine assets that can be used for production and/or storage.

Ultimately, at the other end of the spectrum, the processed products must reach customers, whether in the chemical industry or through gasoline distributors to retail stations. If it is not coming out of the pumps and tanks, the whole supply chain reaches limits, and this is reflected in the differences in global oil prices.

Limits to What Governments and Regulators Can Do

With this reality, government or regulatory intervention can only do so much. Sub-zero spot oil prices are similar to sub-zero interest rates in that sense, outside intervention is very limited. For the financial firms in 2008, the idea of too big to fail emerged and it seemed somewhat arbitrary which companies received bailouts, and which ones collapsed.

In oil and gas and energy services, the threat of going out of business is real and unfortunately is occurring. This is especially true for companies focused on specific segments of upstream and those that service them like we are seeing in the Permian Basin in Texas with US shale producers.

The biggest players have diversified production and vertically integrated businesses and do not suffer from the levels of financial leverage (debt) that are part of the operating model of Wall Street banks. Indeed, from a liquidity perspective, many of the majors have large amounts of cash and had announced more share buybacks and continued dividends earlier in Q1.

Without unmanageable debt levels and with enough liquidity, there will not be any forced marriages between big and big like in the financial crisis. There will however still be M&A and there will be restructuring, and at these price levels, the pressure will be to act quickly and decisively. Perhaps more quickly than during the last two downturns due to the unprecedented breadth of the global demand decrease.

Managing the Impact: Put Your People First

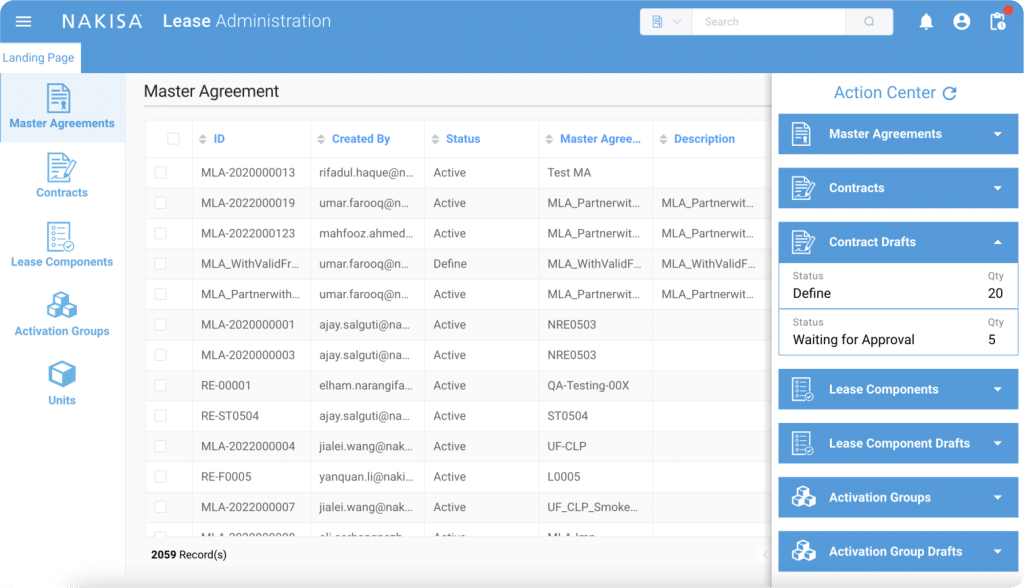

As stated earlier, the industry is underpinned by real assets and real people held together by an interlocking arrangement of agreements and interdependencies. Of all the consequences of disrupting this structure, the most painful is the effect on people and trying to manage the necessary changes to full-time and contracted staff. Indeed, implementing cost models associated with low forecasted price models is bound to involve restructuring in its many forms as will any M&A and large sales.

While working on the cost side of the equation in the immediate term best practices would preserve as much of the revenue side as possible. Identifying and retaining talent through reorganizations driven by cost models or post-merger synergies is one key to protecting this aspect.

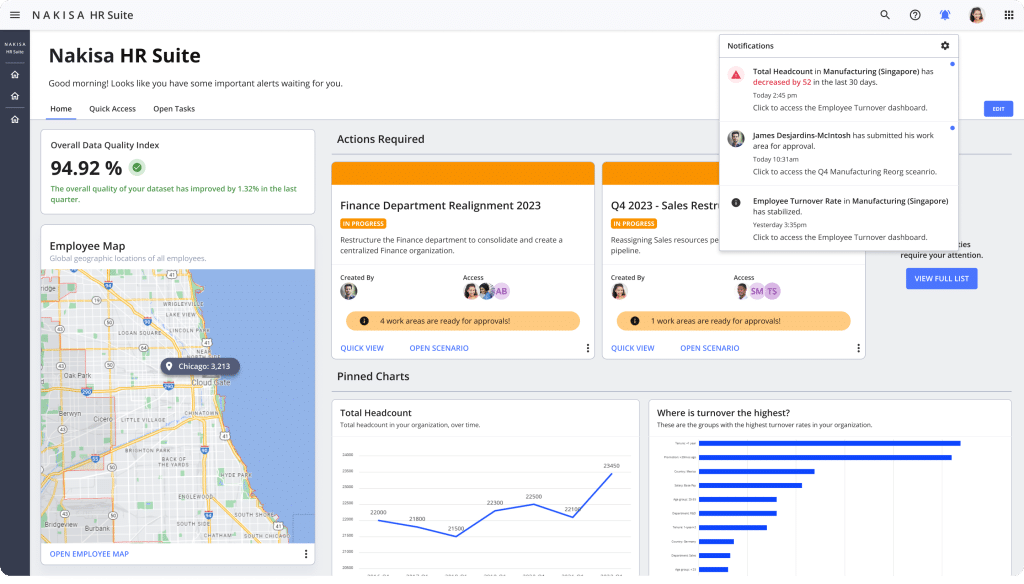

Thankfully, not all the changes that have occurred since the last two downturns have been negative. Advances in digitalization and cloud technologies have unlocked the ability to inform decision-makers with near-real-time information and see the effects of different scenarios and how they will cascade and impact top talent and key positions.

The idea of adopting new technology and implementing it in the middle of cost controls and a price shock may seem counterintuitive. The consequences of proceeding without the information provided are far more dangerous both on the immediate cost side and the longer term revenue side as inefficiencies waste time and money in hitting the goals and lost talent and key employees undermine future success.

Nakisa Hanelly can help support your organization through this period. Learn more about Nakisa Hanelly here, or alternatively, request a demo to experience it firsthand.